The Channel Crossing Gamble: Historic ‘One In One Out’ Deal

On Thursday morning, an Air France plane touched down at Charles de Gaulle Airport carrying what might be the most politically significant passenger of the week – an Indian national who’d crossed the English Channel in a small boat just weeks earlier. He became the first person deported under the UK-France “one in one out” pilot scheme, marking what Home Secretary Shabana Mahmood called “an important first step to securing our borders.”

The irony wasn’t lost on observers that this historic moment came wrapped in legal challenges, with another deportation flight grounded by the High Court just hours before takeoff. Welcome to modern migration policy – where grand political gestures meet the messy reality of human rights law.

A Deal Born of Political Necessity

The “one in one out” arrangement represents a dramatic pivot from the previous government’s Rwanda scheme – a policy that managed to cost taxpayers hundreds of millions whilst achieving the remarkable feat of never actually deporting anyone. Under the new French deal, for every migrant Britain returns to France, it accepts one pre-assessed asylum seeker with legitimate UK connections.

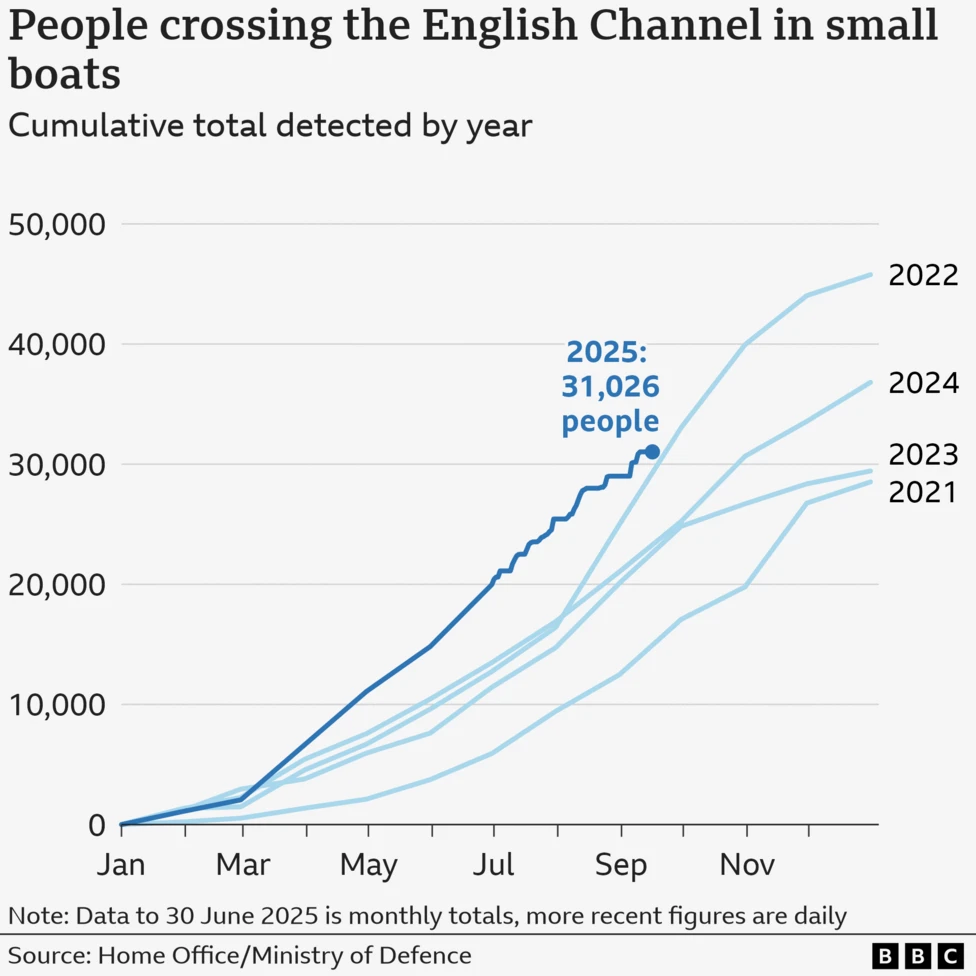

The numbers driving this policy shift are stark. Since August, roughly 5,590 migrants have reached British shores in small boats. This year’s total has already hit 30,000+ people, making it the highest figure for this point in any year on record. Politicians on both sides of the Channel are feeling the heat.

Home Secretary Mahmood was blunt about the message she wanted to send: “If you enter the UK illegally, we will seek to remove you.” It’s the kind of tough-talking rhetoric that plays well in focus groups, but the reality on the ground is proving rather more complicated.

One in One Out is better than the Tory Rwanda project

Tory Twatwaffle Chris Philp was on BBC Radio4 the World at One news programme extolling the virtues for their failed Rwanda plan. One of the most glaring problems with Rwanda was the capacity. Rwanda could only accommodate 300max asylum seekers per year, in fact after the Court of Appeal ruling Sir Kier Starmer stood at the dispatch box and said this:

“When the Government first announced this gimmick, they claimed Rwanda would settle tens of thousands of people—tens of thousands of people. Then the former Deputy Prime Minister quickly whittled it down to mere hundreds. Then the Court of Appeal in June made it clear there is housing for just 100.”

In fact, the 100 figure was an initial figure from the court, then the National Audit Office chimed in by saying:

Rwanda could only take 200-300 people per year at a cost of £600m

So for people like Chris Philp, let’s do some basic maths:

Rwanda: 300 people a year for 5years= 1500max

One in One Out: 50 per week until June 2026 (40 weeks)= 2000

So that’s 500 more people over a shorter period of time. Plus, the people that will be coming to the UK will have connections here – family etc. So the usual Right wing rhetoric of “we dont know who these people are” just wont wash, the incoming migrants will need to prove who they are, so why would they destroy their documentation?

How the System Actually Works (In Theory)

The mechanics are straightforward enough on paper. Anyone crossing the Channel gets detained, and within roughly two weeks, officials coordinate with their French counterparts to arrange return flights. Meanwhile, France sends over asylum seekers who’ve already been assessed as having strong cases for UK protection – people with British family connections or other compelling reasons to be here rather than there.

It’s a neat solution that promises to address multiple headaches simultaneously. Britain gets to reduce asylum accommodation costs (currently running at about £8 million daily for hotel bills alone), whilst France moves some asylum seekers to their preferred destination. Everyone wins, right?

Well, not quite.

Legal Reality Bites Back

The scheme’s debut week provided a masterclass in why immigration policy rarely survives contact with the real world. Just as officials were congratulating themselves on the first successful deportation, the High Court stepped in to block the removal of an Eritrean man who’d claimed modern slavery protection just hours before his scheduled flight.

Mahmood’s response was telling – she vowed to fight “vexatious, last-minute claims.” It’s the kind of language that suggests she views legal protections as inconvenient obstacles rather than fundamental safeguards.

Eleanor Lyons, the UK’s independent anti-slavery commissioner, wasn’t having it. She expressed being “deeply concerned” about the home secretary’s words, warning that dismissing the system as being abused creates a “tool for traffickers to use with those victims that they are exploiting.”

The Eritrean case perfectly illustrates the problem. Eritrea remains one of the world’s most repressive states, with widespread forced conscription that international observers consider slavery. Yet determining whether someone’s been trafficked or is simply seeking asylum takes time – something the government’s two-week processing window doesn’t easily accommodate.

The Deterrent Myth

Central to the entire scheme is the assumption that swift returns will make people think twice about attempting the crossing. It’s a theory that sounds plausible in Whitehall briefing rooms but has a patchy track record in the real world.

Research on migration deterrence consistently shows that people fleeing persecution or extreme poverty don’t tend to make careful cost-benefit calculations about their journeys. Many aren’t even aware of specific policies in destination countries, or they discount the risk of return against the certainty of danger back home.

The continued high numbers of crossings since the deal was announced suggest deterrent effects may be limited. Moreover, the scheme only applies to those whose asylum claims are deemed inadmissible – meaning individuals from places like Afghanistan or Syria with strong prima facie cases for protection may still be allowed to remain whilst their claims are processed.

The message becomes rather muddled when potential migrants can’t easily predict whether they’ll fall into the One In One Out category.

European Politics and Unintended Consequences

The UK-France deal exists within a broader European context that’s less supportive than the photo opportunities suggest. An internal EU document leaked last December revealed that many member states consider returns agreements with post-Brexit Britain “unacceptable.”

Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta and Spain have all raised objections to the bilateral arrangement, partly because they’re worried about how it might affect them. Southern European states, already bearing the brunt of Mediterranean arrivals, fear that successful UK-France cooperation could set a precedent for other northern European countries to negotiate similar bilateral deals, leaving them holding even more asylum seekers.

It’s classic European politics – everyone wants to solve the migration crisis, just not in their own backyard.

The Human Cost of Policy Theatre

Behind the political positioning and legal wrangling are individual stories that illustrate both the promise and problems of treating human lives as tradeable commodities. The Indian national who became the first deportee represents thousands who’ve made similar journeys, often paying smugglers their life savings for a place on overcrowded boats.

Indian nationals represent a growing proportion of small boat arrivals, many fleeing religious persecution or economic desperation in regions like Punjab. They’ve often spent years moving through Europe, seeking stability and opportunity. For such individuals, return to France may simply mean continuing their journey through different routes rather than giving up entirely.

The scheme’s humanitarian provisions supposedly protect those with genuine asylum claims, but determining who falls into which category of One In One Out within tight timeframes presents significant challenges for overwhelmed officials and legal representatives.

Economic Realities vs Political Promises

The government has committed to paying France substantial sums for enhanced border security and returns cooperation. These costs need weighing against potential savings from reduced asylum accommodation whilst providing more dignified treatment for those granted protection.

However, critics of One In One Out question whether the numbers involved will make any real dent in costs. With thousands continuing to arrive monthly and the scheme operating One In One Out, net reduction in accommodation pressures may be limited. The complexity of coordinating assessments between two different asylum systems could generate its own administrative headaches.

There’s also the small matter that the scheme does nothing to address the fundamental drivers of migration – war, persecution, and economic desperation that push people to risk their lives in Channel crossings.

Crystal Ball Gazing

As further deportation flights are planned for coming weeks, several critical tests await. Legal challenges seem likely to multiply as lawyers identify vulnerable individuals wrongly selected for return. The government’s indicated it will appeal court decisions and limit time for legal challenges, setting up potential confrontations between executive and judicial authority.

The success of the reciprocal element also remains unproven. The first asylum seekers from France are expected to arrive in coming days, beginning the other side of the exchange. How well this works will determine whether the deal provides genuine mutual benefits or simply redistributes challenges between two countries.

Most crucially, the scheme’s impact on crossing numbers will become clearer over coming months. If arrivals continue at current levels despite the returns policy, questions about effectiveness and value for money become inevitable. Conversely, any significant reduction could strengthen arguments for expanding cooperation to other European partners.

The Bigger Picture of One In One Out

The UK-France deal represents a pragmatic attempt to manage an intractable challenge through bilateral cooperation. Yet as the first week’s legal troubles demonstrate, the intersection of migration control, human rights, and judicial oversight remains as complex as ever.

Whether this “one in one out” gamble pays off may determine British immigration policy direction for years to come. The Channel waters continue beckoning those seeking better lives, whilst politicians on both sides grapple with balancing humanitarian obligations against domestic political pressures.

In these ancient maritime crossroads, the age-old tension between movement and control plays out daily – in policy chambers and rubber dinghies alike. The first deportation flight may have taken off, but the real test of this policy experiment is only just beginning.

One thing’s certain – immigration policy remains the graveyard of political reputations, where good intentions meet harsh realities, and where the gap between what sounds good in Westminster and what works in the real world continues to provide plenty of material for future blog posts.