Tim Montgomerie and Reform Policies: The Stats & Facts

When political commentator Tim Montgomerie joined Reform UK, it raised eyebrows across the British political spectrum. His long record of right-wing advocacy and flirtation with illiberal ideas offers a revealing lens through which to assess Reform UK’s policies.

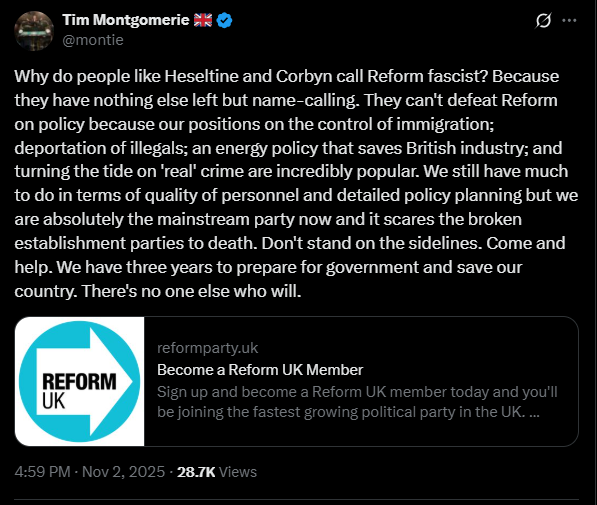

So imagine my surprise when Tim challenged anyone to debate him on Reform policies – Posting this:

Challenge accepted Tim, and I’ll try to spell out the direct comparisons between Fascist Nazi Germany, Mussolini’s Italy, & Reform’s policies – see if you can spot them.

Reform: ‘Take back control’ – At what cost?

At first glance, their platform of “taking back control” may sound appealing to those frustrated with Westminster politics, but behind the slogans lies a set of proposals that could erode civil rights and destabilise democratic safeguards, most alarmingly, the party’s call for Britain to leave the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

This post explores how Reform’s vision, amplified by figures like Montgomerie, risks dragging Britain towards authoritarianism, and why abandoning international human-rights protections could make it almost impossible to reverse such a slide through democratic means. I also incorporate polling and expert legal analysis to show how misaligned Reform’s gamble may be with public opinion and constitutional norms.

The irony of Montgomerie’s position, is that the ECHR protects the freedom to practise religion, especially when Montgomerie celebrated the rise of the religious right

What Do British Voters Think About the ECHR?

Public opinion is often misrepresented in political debates. But when properly polled, a consistent picture emerges: a modest but clear plurality favour staying in the ECHR.

- A YouGov poll in June 2025 found 51% of British adults saying the UK should remain a member of the ECHR, while 27% said it should withdraw. (YouGov)

- Another poll in 2024 showed 54% in favour of staying in, 23% in favour of withdrawal, and 23% unsure. (YouGov)

- An Amnesty International / Savanta poll found that 57% of UK adults said the UK should remain part of the Convention, with only 22% supporting withdrawal. (Amnesty UK)

- A More in Common survey indicated only 23% support for leaving, whereas 49% wanted to continue membership. (More in Common)

One caveat: poll responses vary depending on how the question is framed. When the question emphasises migration control, for example, support for reform or replacement of human rights frameworks tends to rise. (Mark Pack) But when asked directly about the ECHR itself, the pro-remain view holds steady.

In short, although some voters are receptive to rhetoric about “taking back control” from Strasbourg, strong majorities consistently resist the idea of fully exiting the system.

What Legal Experts Warn: Withdrawal Is Not Simple, and It Risks Constitutional Chaos

1. Treaty Exit Powers vs Domestic Law

- Article 58 of the ECHR allows states to “denounce” (i.e. leave) the Convention with six months’ notice. (Institute for Government)

- In the UK the ECHR is embedded into domestic law via the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA), which gives effect to Convention rights in UK courts. (Consoc)

- Simply withdrawing from the ECHR via prerogative powers would not automatically repeal the HRA; that requires explicit parliamentary legislation. (Consoc)

- The Supreme Court in R (Miller) v Secretary of State held that the executive cannot frustrate legislation that Parliament has enacted. Thus, the government cannot unilaterally override or invalidate the HRA (or other rights protections) simply by leaving an international treaty. (Consoc)

Thus, although a government could denounce the ECHR externally, dismantling the domestic legal protections tied to it demands bold legislation and would likely prompt legal challenges.

2. Devolution & Northern Ireland Constraints

- The ECHR is woven into devolved law: the Scotland Act 1998, the Wales Act 2017, and Northern Ireland’s constitutional arrangements all assume human rights obligations. (Consoc)

- The Good Friday Agreement requires that the ECHR be enforceable against public bodies in Northern Ireland. A UK withdrawal could risk breaching that accord unless the terms are renegotiated. (Prospect Magazine)

- Other international treaties, including the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement, indirectly reference human rights frameworks, so pulling out could create cascading legal and diplomatic problems. (UK & EU Centre)

3. Removal of Rights Safeguards = Political Hazard

- Citizens cannot appeal to Strasbourg if domestic courts deny relief.

- Governments could legislate to curtail free assembly, privacy, dissent or due process more freely.

- Political minorities, opposition media, or dissenters lose the external protection that helps to prevent abuses.

Reform’s strategy seems to gamble that once those gates are removed, future generations will manage to re-establish them by democratic means, but history tells us that power, once entrenched, is rarely relinquished easily.

Reassessing the Hitler Comparison: Why It’s More Than Hyperbole

- Hitler’s regime in Germany gradually dismantled independent courts, eroded civil liberties, controlled media, and suppressed opposition, all under parliamentary facades early on.

- Removing binding human-rights constraints is precisely how future leaders could begin that same process in a UK context: one government to “clean up” dysfunction, another to centralise, another to eliminate constraints altogether.

- Without the ability to appeal to a supra-national court like Strasbourg, citizens would be wholly reliant on domestic institutions, which Reform explicitly aims to erode.

- Once legislation is passed (say, curtailing protest, press checks or judicial review), reinstating those protections would require either the goodwill of successive governments or constitutional upheaval, both unlikely under entrenched power.

In other words, Reform UK is not guaranteeing a dictatorship, but by attacking the legal architecture that blocks executive overreach, they are clearing the path for illiberal drift. Montgomerie’s embrace of illiberal democracies like Hungary only reinforces how similar methods may be normalised over time.

Key Takeaway

Even Conservative-friendly pollsters show that most Britons prefer to remain under the ECHR’s protection. And even if a Reform government tried to withdraw, constitutional and legal realities make implementation extremely difficult. The risk is not theoretical: once the safeguards are hollowed out, the reversal would be painful, unpredictable and potentially unchecked.